Women in art: Dorothea Tanning

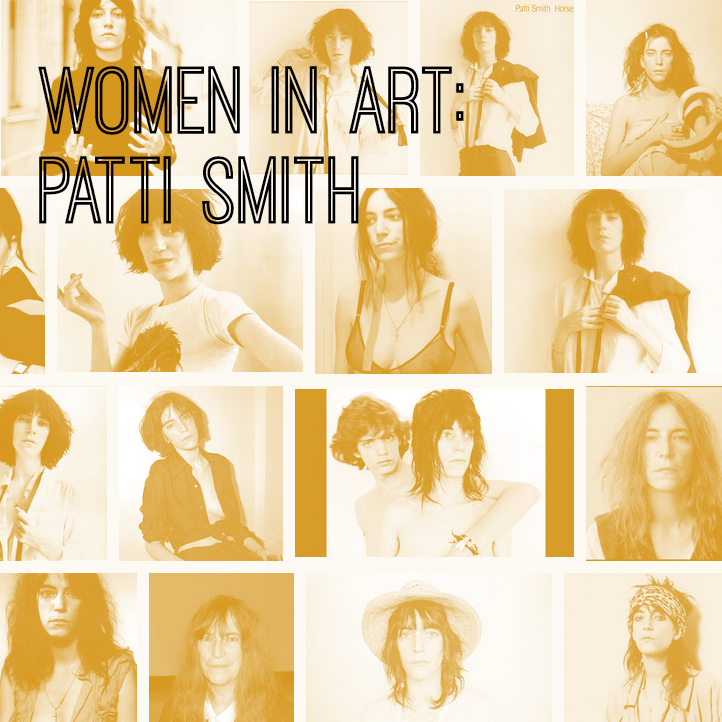

Women in art: Patti Smith

By Jasmine Mansbridge

Patti Smith is a writer, performer and visual artist, often affectionately referred to as the “grandmother of punk”. She was born in Chicago on December 30, 1946 and is still touring and creating today. She grew up in rural New Jersey, moving to New York in the 1970’s. It was during these years, living with fellow artist and friend Robert Mapplethorpe, that she soaked up the atmosphere of the 1970’s experimenting with various art forms, including writing poetry and creating artwork.

My quest for information about Patti went as it usually does, “watching” YouTube clips while I painted, listening to interviews and reading whatever information might be available. I also read Patti’s memoir Just Kids, which she wrote in 2010. The book documents not only her own journey as a young emerging artist, but also her complex relationship with fellow creative Robert Mapplethorpe. Patti Smith’s written work is a pleasure to read. She has a natural way with words. She draws you in to her inner world and connects with readers on many levels.

On being in a relationship

Patti speaks openly about the key relationships in her life. Reading books Patti says, shaped her ideals about being female, romance, relationships and freedom. She was given “The Fabulous Life of Diego Rivera” for her sixteenth birthday and in Just Kids she says, “I imagined myself as Frida to Diego, both muse and maker. I dreamed of meeting an artist to love and support and work with side by side.” These words indicated to me Patti’s romanticised ideal of a relationship.

Patti and Robert Mapplethorpe’s story is an intriguing one. They met not long after she arrived in New York and their relationship became one that was pretty much based on Patti’s muse/maker ideal. Their common bond as artists meant that they were able to maintain a bond and a deep friendship throughout their lives, even after their physical relationship changed.

In the early days, Patti worked various day jobs to support Robert while he worked on his art full time. She saw this as her contribution to his career, it wasn’t until later on that she was able to work of her own material full time.

The passing of time saw Patti and Robert’s relationship change, as Robert came to terms with his homosexuality. They continued to live together and support each other, however, agreeing to do so until such point at which they had both become independent of each other.

A high point in Patti and Robert’s relationship was the exhibition they had together at the Robert Miller Gallery in 1978. This was to be Patti’s first exhibition in the Gallery and the only time the two exhibited together. After this exhibition, they both went their separate ways, having kept their promise to see each other safely to success. Patti went on the road with her band and Robert’s focus became more and more on his photography, which was bringing him high acclaim.

Patti’s next significant relationship was with Fred Sonic Smith. Fred and her were both musicians and they met when she was touring. They bonded over a common love of poetry and Patti says it was Fred who she decided to marry in 1980, (the joke was apparently that she married Fred because she wouldn’t have to change her surname).

Patti talks warmly of her relationship with Fred and their move to the suburbs of Detroit. She said this time had been similar in feeling, to her early days with Robert Mapplethorpe. Starting with nothing but a few favourite things for possessions, and then waiting to see what the future would bring. Patti and Fred went on to have two children, Jackson and Jessie, and settled into a routine dictated by their domestic needs.

The next space in time was one of deep sadness for Patti. These two important men in her life both passed away. Robert died first of HIV AIDS in 1989 and then her husband Fred of heart failure in 1994. In this same period, Patti’s brother and her pianist also died. At this point Patti decided to take a break from her creative career to focus on bringing up her two children, moving from Detroit back to New York.

It is truly moving to hear Patti’s first hand accounts of these significant relationships as she shares them in her memoir. It is Patti’s openness and vulnerability that further endears her to her fans. One gathers that in her life Patti loves deeply, loyally and unreservedly. My observations are that Patti has always been an equal partner in her relationships. She talks about relationships in ways that take responsibility for her own actions in them, right or wrong.

I took away from this the importance of honesty and complete acceptance of another person. To allow each other freedom and space, for both difference and growth. Of course this is always easier said than done. But, as in Patti’s case, the rewards are reaped in having that understanding and room to move, granted to one’s self as well.

On being creative

Patti says that as a child she was not gifted, but she was imaginative and that she was rewarded at school for being so. She says of being an artist that, “I had no proof that I had the stuff to be an artist, though I hungered to be one.” From childhood Patti had devoured books and poetry and she talks about having the sense that there was something for her to say as an artist, and that somehow she would find her voice.

Patti has ended up a household name for being one of the first “poet” musicians. She was basically a published poet who went on to add rock/punk musical layers to her words. She landed a record deal and released the debut album “Horses” in 1975. Her work subsequently had a major impact on both the punk movement and the associated musical scene, especially in America and England. Patti became an icon to subsequent generations of punk rockers. Patti is also a visual artist and has been represented by the Robert Miller Gallery since 1978.

What struck me ,the more I researched Patti, is the calm she seems to have maintained about being an “artist”. Even when she felt like she had nothing to show for the fact. She never seems to have appeared anxious or desperate about having her work seen or heard. It seems like her sense of self was always there, unwavering. She credits her association with Robert Mapplethorpe for this attitude.

In her dress and her manner she never appears to be overly concerned with material things. It is her books and her tools such as pencils and notebooks that she treasures most. These things all speak to me of a deep inner self confidence.

During the early years of her career Patti seems to have met the right people at the right time. People who encouraged her and gave her opportunities. Patti says in her memoir that at times her success had seemed to come a bit too easily, and that she hadn't wanted that. Patti actually turned down the first opportunity to publish her poems because she felt she had not earned the right and “the spoils of battle were not yet to be hers”.

Of all the knowledge I gleaned from Just Kids, there is one quote that will remain for me: “That we are mortal, our work is not, do your best work, let your work stand alone”. This is wonderful advice for any artist at any stage in one’s career.

Patti has gone on to have a lifetime of achievement. In 2005, Patti Smith was named a Commander of the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the French Ministry of Culture and in 2007 she was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, both fitting honours for this artist who has lived true to her ideals of creating original work throughout her lifetime.

On being a woman

It is hard to not make a comment about Patti’s appearance. It is one of the things about her that has impressed me. With her strong nose and thin frame, Patti has an androgynous, raw beauty which adds to the uniqueness of her character. Throughout her life she appears to not give a damn about what others think. The original “messy hair, don’t care” girl. I see much of a current “it” girl, Alexa Chung mirrored in her look. Rail thin with bangs and over sized t-shirts (I wonder what Patti thinks of that?).

Patti often describes herself as having been an outsider and a wallflower in her youth. As a young girl she found the changes in her body as she grew, awkward and unwanted. She says she wished she could have stayed a child forever, just like Peter Pan.

In her role as artist Patti has never made an issue of her gender. She talks about this as being a deliberate act on her behalf, so she could be a kind of “third” gender. She sought to call attention to herself as an artist, not as a woman. Patti simply dressed and performed in the spirit of her male rock and role models, as if no alternative had ever occurred to her. In the process, she obliterated the expectations of what was possible for women in rock, and stretched the boundaries of how artists of any gender could express themselves. Patti saw her music as a way to be genderless and many of the lyrics of her songs are ambiguous with regards to meaning and sexual references.

Another fact about Patti that I found interesting is that she was not a drug user. And I am not alone in presuming that with her waif like appearance and with the culture of drug use in her time, that she would of been “on” something. Her peers back in the day also presumed she was a drug user. Patti didn’t even smoke, although she modelled for photos with a cigarette to perfect a “look”. Patti had the occasional high, but had always felt that drug use wasn’t for her. Patti is the perfect example of why stereotyping people is unfair (and perhaps her choice to not use drugs is a contributing factor in her success even today). Patti was a women who blazed a trail for many other artists to follow.

On being a mother

Patti says that she had felt it a cruel betrayal of nature when after a brief experience with another boy as inexperienced as herself, she found herself pregnant at age nineteen. She speaks beautifully and poignantly of this time in her memoir. She went on to have the baby, adopting it to a couple who could not have a child of their own.

When she became a parent again later in life, Patti took the role seriously, leaving the professional music scene to take care of her children. I admire her decision to do this and once again it speaks of her confidence in herself and in her abilities as an artist.

Patti says that it had been perfect timing for her and Fred to marry and for them to become parents. She had started to feel like she had accomplished her mission with her music and that there was no more room for growth just being on the road.

Later on, after her husband Fred’s death, Patti was left a sole parent to her children. Patti says that her years spent mostly at home being domestic were not wasted and had made her a better human being. Upon reflection she states that being a mother had made her more empathetic and more knowledgeable about the world. That the discipline of caring, cooking, cleaning and washing etc had been good for her. It was also in this period that she began to focus on her writing. Piecing together the story that was to become her memoir.

There is a beautiful quote from “Just Kids”, when Patti talks about being pregnant with her daughter Jessie and visiting Robert for the last time before he passed away. He was gravely ill and she had travelled from Detroit with Fred to New York to spend time with him. Patti recalls, “Within that moment was trust, compassion, and our mutual sense of irony. He was carrying death within him and I was carrying life. We were both aware of that, I know.”

Patti remains close to her children, they are both musicians and she performs with them on stage when she has the opportunity. She says that through them she feels the presence of their father Fred and that they have been a wonderful gift to her life.

Things to learn from Patti Smith...

When you see Patti performing her music in all her rock and roll glory, you only see one side of her. Dig deeper and her writing and speaking reveals a very different side. Patti talks about this contradiction and says it is true, she is as comfortable screaming down a microphone as she is cooking dinner for her children, or curled up reading a book. She is the same person doing all these things. I found this interesting as it is something I wrestle with sometimes myself, the contradictions within ones self. These contradictions Patti says give her the platform to create meaningful work.

I could go on, but in short, here are the most useful things from I gleaned from Patti’s story:

- Remember to keep focused on doing your best work as an artist (not always the most popular work).

- Try not to get caught up in being competitive with other creatives and be creative in whatever way comes to you.

- Avoid wanting the “celebrity” of art, without the work and the sacrifice.

- Remember that it may take a lifetime to work out what it is you want to say, and that what you want to say might change.

- Be prepared for hard times as well as good times.

- Be independent as a women, but also being able to love and be loved.

- Don't let being a women affect your work or how you allow yourself to be perceived.

- It is okay to put your family first when needed.

- You can step back from your creative career and still be successful long term.

- Be your own wise counsel.

- You are mortal, your work is not, so make your work your best.

For more about Patti Smith, check out this video, and this one, and this one; this article at The Guardian; some info about Fred Sonic Smith; and of course, her memoir, Just Kids.

————-

Jasmine Mansbridge is a painter and mum to five kids. She regularly blogs about the intersection of creative work and family life at www.jasminemansbridge.com, and you can also find her on Instagram @jasminemansbridge.

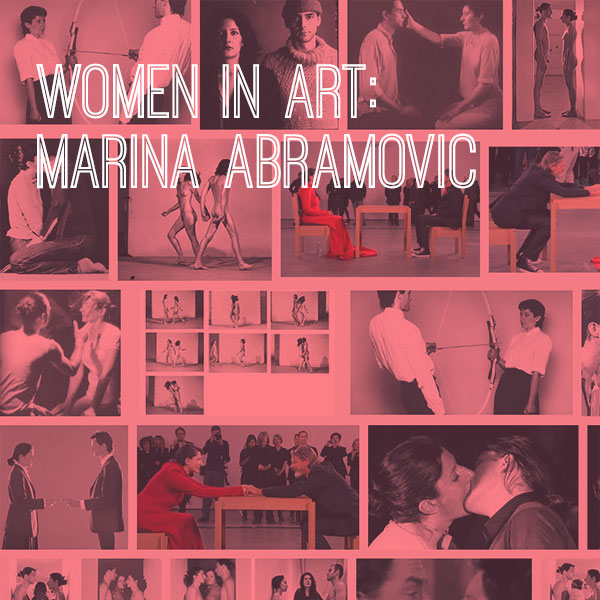

Women in Art: Marina Abramovic

One very well documented relationship between two artists is that of the Yugoslavian born Marina Abramovic and the German born Ulay (Frank Uwe Laysiepen). Marina and Ulay’s relationship was both the subject of and the basis of most of the inspiration behind their art making. The couple shared a birthday, the 30th of November and upon meeting felt they had an immediate connection. They later said that destiny had brought them together. Theirs was a relationship which Ulay himself describes as having “a degree of symbiotic equality far from commonplace”.

Marina Abramovic is a woman with a significant place in the history of modern art. She is often referred to as the “grandmother of performance art”. Her work titled “Rhythm O” (1974) helped earn her a reputation as a fearless performer. A year after this piece was made Marina met Ulay, and she has said of their meeting that, “he was a blessing and in a way he saved me, as those performances would have destroyed my body”. Prior to working with Ulay, Marina’s work had been largely self destructive, involving both pain and danger.

So the two began performing together, using their bodies as a both a medium and a tool. Marina and Ulay examined the many aspects which make up a domestic relationship, exploring issues like gender, trust, intimacy, ego and artistic identity. They often dressed as twins and their aim was to completely absorb one another. They pushed many boundaries to try and to morph into one “being’ as much as possible. Marina has said that together they were like a “third identity”. They lived solely from a van for five years, in which they travelled across Europe, their Manifesto at that time being: no fixed living place, permanent movement.

Marina and Ulay made approximately ninety art pieces together. To give you an idea of what these performances actually looked like, here are some of the actions that some of their pieces entailed:

- with mouth upon mouth, they breathed in and out shared air until they both eventually lost consciousness.

- running into and colliding repeatedly into each other, (whilst naked).

- standing naked opposite each other in a doorway, the audience having to walk between them to enter the room.

- sitting back to back for seventeen hours with their hair intwined.

- holding a bow and arrow between them, increasing the tension over time, Marina was at the arrow end.

The above gives you an brief idea of the lengths that Marina and Ulay went to test the limits of their oneness, through the medium of performance. (If you are interested, a search on YouTube reveals video clips of most of the above performance pieces.)

The intensity with which they conducted their relationship took it’s toll, however, and Marina and Ulay have said that they began to feel the “tightness of their ideologies begin to unravel”. Marina has said that it was almost like the better their performances became, the worse their personal relationship became - that in private, they started to lose their oneness. Their relationship broke down and was eventually no longer monogamous. Finally, after twelve years together, they decided to go their separate ways. They had lived and worked in what can only be described as the most deliberate of relationships. So as a way of celebrating, commemorating and honouring their relationship, they decided to do one last “performance” together. In 1988, they each began walking from opposite ends, the approximately 2,000 miles of the Great Wall of China. Marina starting from the sea and Ulay from the desert. They met in the middle and symbolically separated from that point. Ending an epic partnership. Ulay married a new partner not long after the walk's conclusion, cutting off any future possibility of an easy reunion.

Marina talks openly of her struggles after her relationship with Ulay ended. She has said she felt "fat and forty", and empty after losing both her partner and her work, the two having been intertwined for so long. She said she needed to find her femininity and her place again. Ulay and her had had traditional roles within their relationship, him being responsible for the money, applying for grants etc, while she washed and cooked. Marina says that it took her some time to get her head around financial and business related matters when their relationship ended. She talks of the suffering of that time and how eventually it all had made her stronger.

This now iconic photograph was taken on the opening night of a retrospective Marina held at MoMa in 2010, titled, “The Artist is present”.

For three month,s Marina sat at at a table in MoMa, looking across at strangers as they took the time to sit opposite her. This photograph captures Marina’s deeply moving reaction to Ulay when he arrived unexpectedly at her performance. She breaks protocol and reaches out to him across the table between them. This image, taken years after their relationship ended, says much about the strength of the bond they once shared. Marina says of this, “The moment he sat – everyone got very sentimental about it, because they were projecting their own relationships on to us – but it was so incredibly difficult. It was the only time I broke the rules."

Although Marina has said that meeting Ulay “was a blessing”, and they achieved much during their time together, in her artist manifesto she states (more than once) that, “an artist should avoid falling in love with another artist”. Marina has based this statement on her own life experience, (she recently divorced an Italian artist). When asked about relationships in a recent interview with the Guardian , this was her answer:

"No. Of course, I dream to have this perfect man, who does not want to change me. And I'm so not marriage material, it's terrible. But my dream is to have those Sunday mornings, where you're eating breakfast and reading newspapers with somebody. I'm so old fashioned in real life, and I'm so not old fashioned in art. But I believe in true love, so perhaps it will happen. Right now, no, I have no space. But life has been good to me. Lots of pain. But it's OK.”

Marina Abramovic is an all-round fascinating person and the more I have learnt about her, the more curious I have become. Her work has a timeless quality as it deals with many things - the unchanging aspects of human consciousness and the relationship between body and mind being recurring themes. After almost forty years she continues to make relevant, groundbreaking, thought-provoking works. I must say I feel encouraged by her long term dedication to her art. Some days, when I feel like I am not progressing in my own work at the pace I would like, an artist like Marina reminds me of the fact that I have plenty of years yet to make my best art.

In 2014, there was a documentary made on Marina’s life and work so far. As I said when I started writing this post, the subject which is Marina Abramovic is a well documented one and there truly is a plethora of information out there if you want to know more about her.

Australian readers might be interested to know that Kaldor Public Arts and MONA (David Walsh), are bringing Marina to our shores. She is performing in Sydney and at MONA in Tasmania in June/July this year. No doubt this will be a unique, possibly once in a lifetime opportunity to see the artist in action.

I do hope you have found something to ponder on in this article. I think Marina and Ulay were very brave to use their relationship in such a way and I am not surprised that eventually they went their separate ways. For me my relationship is kind of like my ticket in and out of normality, almost like the hinge I hang off. I can’t imagine the intensity of being in a relationship that is both the subject of and the canvas of my creativity.

I am, as always, very interested to hear your thoughts on all things art and relationships and what works and what doesn’t.

-------------

Jasmine Mansbridge is a painter and mum to five kids. She regularly blogs about the intersection of creative work and family life at www.jasminemansbridge.com, and you can also find her on Instagram @jasminemansbridge.

Women from history: Hilla Becher

Relationships fascinate me. The fact that two people choose each other and then make a life together is pretty amazing. So, when I was asked to write a series of posts about significant creative women from history for CWC, I thought it might be interesting to look at some of the great creative partnerships/relationships in art history... with the idea that there might be something to be learned from them!

In this first blog post I have chosen to look at the relationship of German conceptual artists, Hilla and Bernd Becher. Hilla and Bernd met when they began working together in Dusseldorf in 1957 and they married several years later. Cameras in tow, they adventured about the countryside, united by a shared fascination with the decaying forms of early industrialisation. Over time their singular aim became to preserve what they felt was a disappearing part of modern history. Hilla and Bernd together, were compelled to capture these utilitarian monuments via their preferred medium of photography.

I must admit that it was the photography of Hilla and Bernd and their subject matter that first drew my attention to them. The stark objective way they captured their audience of man made structures, which included water towers, mills and furnaces very much appealed to my aesthetic. The exhibited photographs of these structures were often set into “typologies” or grids, so as to allow for viewers to make comparisons about similarities and differences between the different structures and for them to be able to see the detail and careful workmanship that had gone into the making of many of them.

The Becher’s first began using their documentary style of photography in Germany’s Rhur valley, which was close to home and over the years they then travelled to many other declining industrial centres, in Britain, France, Belgium and the United States.

There is not a lot written about Hilla and Bernd’s relationship outside of the boundaries of their art making. If they lived and worked today, they may have a blog, or an instagram account (!) and so there would be, perhaps, more direct insight into what made them tick as a couple.

So, for the purposes of this post I am relying on mere presumption about the Becher’s personal relationship. They spent decades working together and appear to have consistently shared a singular vision and artistic focus. This is an impressive achievement for one person alone, even more so for a couple. I wonder if the boundaries they imposed on their work contributed to their success in both art and love? If this sustained common goal gave their relationship both stability and longevity?

Hilla and Bernd are also rare in the fact that they appear to be true equals in their art making process. This is apparent when you listen to the talk they recorded for Arch types. Given the times in which they worked, Hilla could easily have only been Bernd’s artistic assistant, and may have accepted that role happily. But, by all accounts theirs was a partnership, a collaboration. The two of them working methodically to create an impressive body of artwork. They obviously valued each others skills and each felt they needed the other to complete the task at hand. They don’t appear to have had solo projects and if they did, they were not the main focus for either of them. This sense of equality surely contributed to their success.

The Bechers felt passionate about the preserving of history and viewed their work as important. I wonder if this dedication enabled them to put aside any differences that may have arisen between them. Was the cause behind their photography greater to them than any kind of competitive artistic ego? In the same way couples will often put aside differences for the sake of their children. I imagine that maybe Hilla and Bernd did this for their works of photography.

Bernd taught photography at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf for 20 years, until 1996. It was due to internal policy, that Hilla was unable to be employed alongside her husband, although she is said to have been instrumental to the running of the photography department. Hilla obviously accepted this and there is nothing I could find written to suggest she was unsatisfied with the arrangement. Hilla’s position highlights the challenge presented to female artists in the past (and lingering into the present). The formidable Becher partnership endured until Bernd’s death in 2007 and since her husband’s passing, Hilla has continued to exhibit their work, using the couple’s existing photographs.

When looking at the Becher relationship I felt there were many questions left unanswered. I wonder if the personal details of their relationship were off limits and if it was something they agreed not to talk about. If this is the case I understand. I am comfortable sharing many aspects of my own life, but I respect my husband's need for privacy and do not talk much about “us”. Hilla and Bernd were certainly are an intriguing couple who produced a flawless body of work. For further reading, I'd recommend this book about the Bechers titled Life and Work by Susanne Lange.

I'm very interested to hear from those of you who are in personal relationships with other artists. Have you ever collaborated on a project? How did that go? What are the ups and downs of this? Tell us on Facebook, Instagram or Twitter.

-----

Jasmine Mansbridge is a painter and mum to four (almost five) kids. She regularly blogs about the intersection of creative work and family life at www.jasminemansbridge.com, and you can also find her on Instagram @jasminemansbridge.

Women from History: Marianne Brandt

By Julia Ritson She made dustpans, clocks, lamps, and light shades and was to become one of the great success stories of the Bauhaus, the German school of design founded in 1919.

Marianne Brandt was first a student then a teacher of metal work at the Bauhaus. Traditionally, Bauhaus women were popped into the textiles department and Brandt had to work hard to be accepted into the metal workshop.

At the time, the master of materials and form, László Moholy-Nagy, was in charge of the metal workshop.

When Brandt first arrived, fancy table top items were the focus of the workshop. These concise silver and bronze pieces were made in 1924. Articles for every day use.

Brandt was the only female student and wasn't immediately welcomed into the male group.

At first I was not accepted with pleasure - there was no place for a woman in a metal workshop, they felt. They admitted this to me later on and meanwhile expressed their displeasure by giving me all sorts of dull, dreary work. Later things settled down, and we all got along well together.

In the late 1920's there was a strategy of trying to integrate art and technology. They were attempting to make art objects for a mass market.

At one point the school needed decent lighting solutions to fit the new design aesthetic and the brief was given to the Metal team to come up with solutions. Here are the adjustable lamps hanging in the weaving workshop, designed by Marianne Brandt and Hans Przyrembel in 1927.

The idea of making lighting fixtures out of shallow glass dishes attached directly to the ceiling probably came about in the metal workshops of the Bauhaus. Also the the idea of combining opaque and frosted glass, of making lighting fixtures of aluminium and of designing ceiling fixtures with glass cylinders appears to have first been thought of in the Bauhaus.

This glass globe was designed in 1926 and manufactured by a firm in Berlin. Good modern industrial design.

The much imitated "Kandem" bedside-table lamp was designed by Brandt in 1927. It was then produced by Körting & Matthiesen in Leipzig. From 1928 to 1932 this company often sought advice from the Bauhaus for its designs of light fixtures and desk lamps. During these years more than fifty thousand Bauhaus designed lamps were sold.

You can buy one today on ebay for US$2,750.

Julia Ritson is a Melbourne artist. Her paintings investigate colour, abstraction and a long-standing fascination with the grid. Julia has enriched and extended her studio practice with a series of limited edition art scarves. She also produces an online journal.

Women from History: May Morris

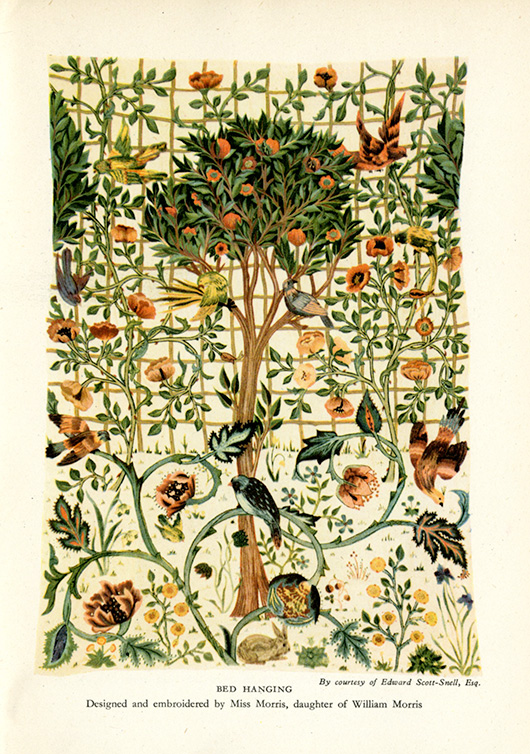

By Julia Ritson May Morris was an embroiderer, jeweller and editor who lived her life overshadowed by her famous father - the arts and craft doyen William Morris.

The Morris family were craft makers who extolled the virtues of a pre-mechanised world. They were living in a world where the word Master had come to mean Master of others, rather than Master of a craft. They preferred the mastery of craft concept.

The Arts and Crafts movement they were part of looked back to the medieval world with a focus on textiles, wood, metal work, and interior design. Plus a little medieval poetry thrown in.

The family business sold medievally themed items to the emerging English middles classes in the late 19th century.

I first came across the work of May Morris in this British Craftsmen book written in the 1940s.

May Morris' work was featured.

The William Morris company resurrected the concept of free-form embroidery. The idea of "Art needlework" highlighted freehand stitching and shading in silk threads to achieve a more expressive result, rather than the formulaic templates of the typical embroidery of the mid-19th century.

May Morris trained at the South Kensington School of Design and at the age of 23 took over the management of the embroidery section of Morris & Co from her father. A very capable young lady.

May Morris went on to write a wonderful book called "Decorative Needlework."

"Chain-stitch has been so called because it imitates, more or less, the links of a simple chain. It is the foremost and most familiar of all similar stitches. It has a very definite character of its own, and though apt to become a little monotonous, is from its laborious and enduring- nature well suited to work that may be subjected to much wear and tear. In the accompanying diagram it will be seen that each little loop grows out of the last; the needle follows the exact direction in which the line of stitches is to lie."

May's insights on colour are worth sharing.

"Of blue choose those shades that have the pure, slightly grey, tone of indigo dye (varying somewhat, of course, on different materials). The quality of this colour is singularly beautiful, and not easy to describe except by negatives : it is neither slatey, nor too hot, nor too cold, nor does it lean to that unutterably coarse green-blue, libellously called ' peacock ' blue ; it has different tones - brilliant sometimes, and sometimes quiet - reminding one now of the grey-blue of a distant landscape, and now of the intense blue of a midday summer sky - if anything can resemble that.

Of reds, we have first a pure central red, between crimson and scarlet (for in the pure colour neither blue nor yellow should predominate), but this is a difficult shade to use; by far the most useful are those 'impure' shades which are modified by yellow, as, for instance, flesh-pink, salmon, orange, and scarlet; or by blue, as rose-pink, blood-red, and deep purple-red. The more delicate of such shades can be freely used where a central red, overpowering in its intensity, cannot. A warning, however, against abuse of warm orange and scarlet, which colours are the more valuable the more sparingly employed, and as dainty little spots of colour treasures indeed.

The most valuable colour next to blue is green, or, rather, equally valuable in its different way, being to some people more restful to the eye and brain.

Here, again, we see the force of the positive and relative value of colours : a cold, strong green, not in itself very pleasing, placed against a clear brilliant yellow, gathers depth and force which it would otherwise lack ; a blue-green may strike the right note in a certain place, but if its use be exaggerated may blemish all. Now, there are certain greens which are brilliant and rich, and, when employed broken with other colours, produce a fine effect; but when a green is to be largely used, it should be chosen of a greyer, soberer shade, such as the eye rests on without fatigue. Avoid like poison the yellowish-brown green of a sickly hue that professes to be ' artistic,' and looks like nothing but corruption, and avoid also a hard metallic green, which, after all, would not easily seduce a novice, as it is very obtrusive in its unloveliness.

Certain definite sets of green will be necessary ; full, pure yellow-green, greyish-green, and blue-green, two or three shades of each. The brilliant pure green that we admire in a single spring leaf is impossible to use in large masses, nor does Nature, whose all-pervading colour is green, give us these acute notes in unbroken mass. You have only to look at the effect of light and shade in a tree in full spring foliage, with the browns and greys of its twigs, to realise this fact: the great masses of green meadow-land, besides showing a variety of colour that may be overlooked in a careless glance, have a tenderness of tone that is quite beyond and above any possible imitation in art.

For a central yellow choose a clear, full colour that is neither sickly and greenish, nor inclined to red and hot in tone. Of impure yellows, pale orange and a warm pinkish shade that inclines to copper are useful, besides the buff and brownish shades that will sometimes be wanted for special purposes. These, I think, include all the yellow shades that you need trouble about. A certain experience is wanted for the successful use of yellow, so that those who take a special delight in the intrinsic beauty of this fine colour will do well to avoid too enthusiastic an introduction of it into their work.

Purple again is one of the 'difficult' colours with which we must, as it were, hit upon the exactly right tones to use. There are two valuable purples - a rather full red-purple, tending to russet, and a dusky grey-purple, which is, if the right tone is obtained, a very beautiful, and, if I may say so, poetic colour."

A poetic lady.

Julia Ritson is a Melbourne artist. Her paintings investigate colour, abstraction and a long-standing fascination with the grid. Julia has enriched and extended her studio practice with a series of limited edition art scarves. She also produces an online journal.

Women in Art: Press photography - then & now

By Liz Banks-Anderson Recently I attended ' Press Photography: then & now', where Photographer and Bowness Photography Prize People’s Choice Award Winner (2010) Melanie Faith Dove discussed with fellow photojournalist Bruce Postle their experiences of working as professional photographers for The Age and how photo journalism has changed in the last fifty to sixty years.

Photojournalists manage to capture in one image many things. These can include the subtleties of emotions and relationships between people, moments of grief and hardship or political statements. Moments in life that can define an era, in one single shot. In an age where anyone can take a camera or their smartphone and press 'capture', the mark of a true photo journalist is an image that is truthful in its spontaneity and resulting authenticity.

The images shared at the talk provided insight into a world past and shed light on issues we continue to confront in the present and will become all the more significant in the future.

Melanie’s work comprises press photography as well as feature work and portraiture, book and magazine covers, to photo essays and news features.. She says to be a photographer, “…you almost have to be a bit nuts.”

Throughout the talk, each photographer shared images from their portfolio that displayed different elements of artistry, be it theatrical, realistic, political or pure fun.

In additon, both Melanie and Bruce offered their perspective on a dynamically changing industry, transformed by new media, digital technologies and the advent of the 24/7 news cycle. They shared the view that in an age flooded by user-generated images, the role of the photojournalist is important “…in shining a light on issues that need to be explored, exposed or preserved for now and future generations. They assist in educating the broader public and perhaps bring about transparency and change,” says Melanie.

The impact of technological advancements on the industry and its work practices has been transformative. With the help of an iPad or the smart phone, press photography is now more accessible to the reader than ever before. But accompanying these new technologies is also the expectation for the professional photographer to be ‘jack of all trades.’ Press photographers can work remotely, with jobs being emailed to them, resulting in, to a degree, a loss of camaraderie and sharing and learning from each other. Melanie says that this has been addressed in part by developing networks elsewhere.

However, new technologies have meant new opportunities as well, producing a variety of images for different purposes, such as online galleries.

What became clear is that behind each photographer’s method, as well as obvious talent, is an element of serendipity. Stumbling upon the perfect shot was all in the timing with stories ‘coming out of left-field.’ There is also an element of self-determination in seeking the perfect image, by placing yourself in the right place at the right time, “I have often given myself jobs, because I want to see and experience things,” said Melanie.

More information about Melanie Faith Dove and her portfolio can be found at her website, and an exhibition of Bruce Postle's work entitled Image Maker is at the Monash Gallery of Art until June 30.

Liz is a communications professional and freelance writer from Melbourne. Liz’s own blog will be launched soon…In the meantime, she’s happy being a twit.